Ever since my husband and I moved there circa 1998, downtown Easton has always been a magical place for me. I have lived there, worked there, dined there, and seen the neighborhood grow and change, businesses come and go.

Easton PA and Phillipsburg NJ were both struggling fiercely then, and fine artists were starting to buy property and set up studios in Easton. A lot of my favorite people came to Easton in this way. Phillipsburg had hoped to redevelop industrial lands (which, as in the trend now, has become warehouses) and attract railroad-related tourism.

For those who are not local, while these two towns are in different states, they are only separated by a river– the Delaware River– and that river is easy to cross, even on foot. When I was covering Phillipsburg as a newspaper reporter, I learned that Phillipsburg residents often referred to Easton as “going to town.” Both regions, in Pennsylvania and New Jersey, have strong agricultural roots so state lines meant little when compared to where the department stores, services, and professionals were.

Even though I do not live in Easton, and have not for the last 20 years, I have lived a mere two miles away from downtown Easton and can still physically walk there it’s so close. The street where I live, and those parallel, all go straight downtown.

I went downtown yesterday for an appointment at the Sigal Museum. Now, as a historian and a proud local history nerd, this alone was a great way to start the day. When I arrived, they had just opened so they weren’t quite ready for me yet. Being gracious hosts, they told me to go play in the museum. I mean visit. Visit the museum.

Before I could reach the exhibits, I had the chance to explore the Arts Community of Easton Small Works Show — which features works by Parisian Phoenix contributors Joan Zachary and Maryann Riker (even if her piece didn’t have her name on it. I recognized it!), (speaking of Phillipsburg) a long-time peer and lover of Barenaked Ladies Claire Jewett who used to own a business in downtown Phillipsburg, and my neighbors, literally the other side of my house, James Cox and Sarah George.

I will be doing two workshops for ACE, at the Easton Area Public Library main branch in July. I believe it’s July 8 I will present a memoir class, and on July 30 we will be working on writing clear nonfiction.

So that was fun… And then it was time to immerse myself in local history.

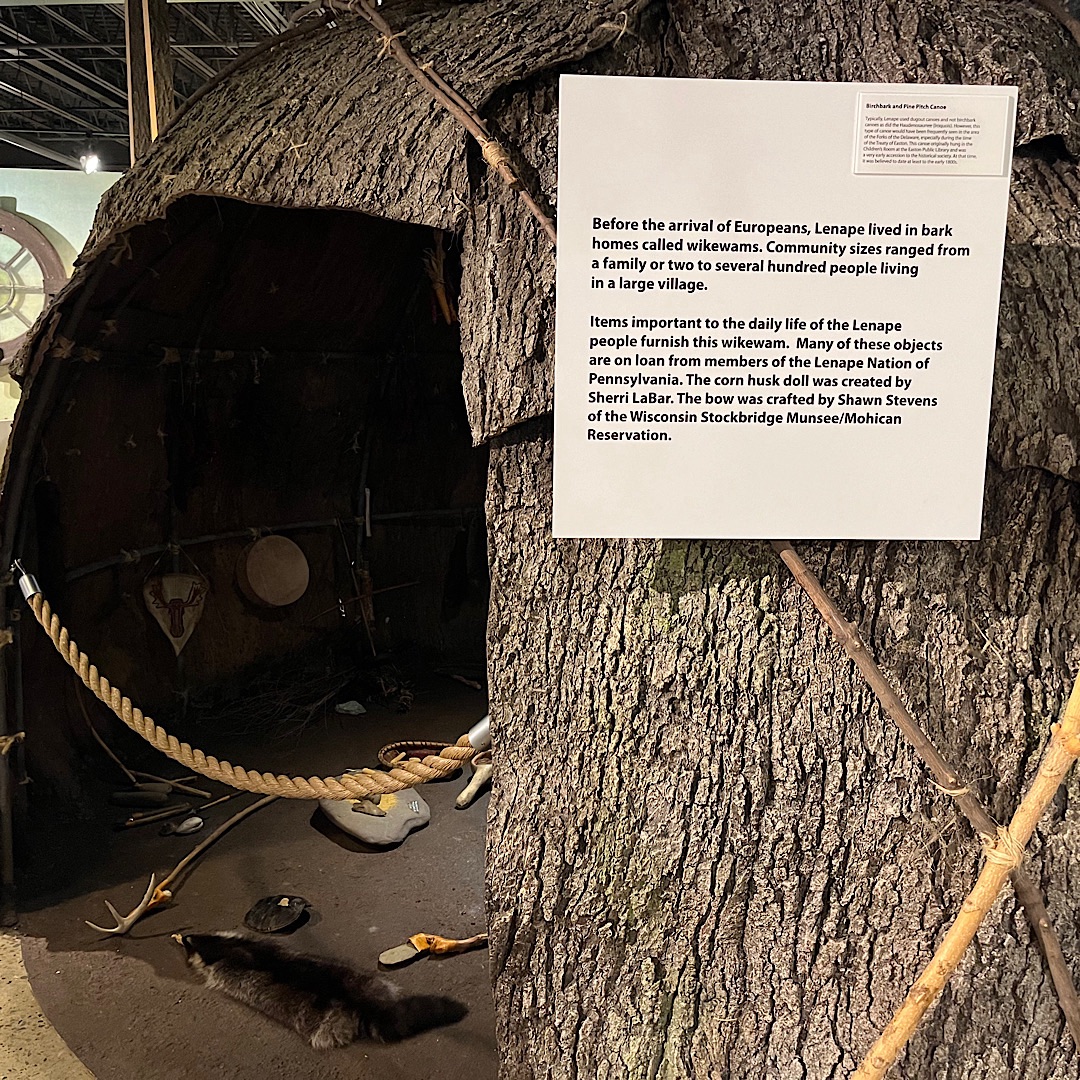

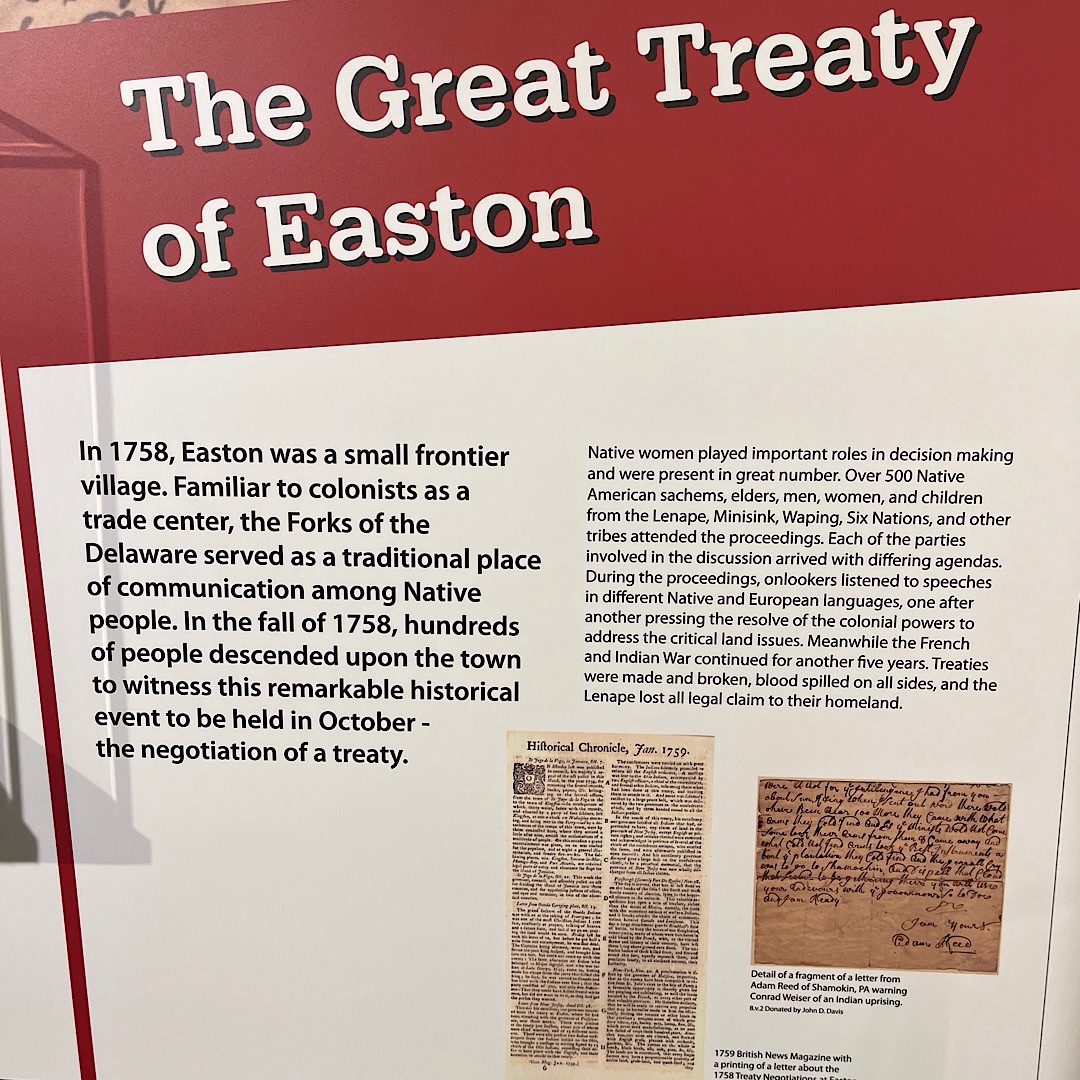

They have a wonderful exhibit about the origins of the two rivers area and the Native American tribes there. And a wigwam/wikewam! I explored the first floor for a while but I had to carefully extract myself before I wouldn’t be coming out again until they closed.

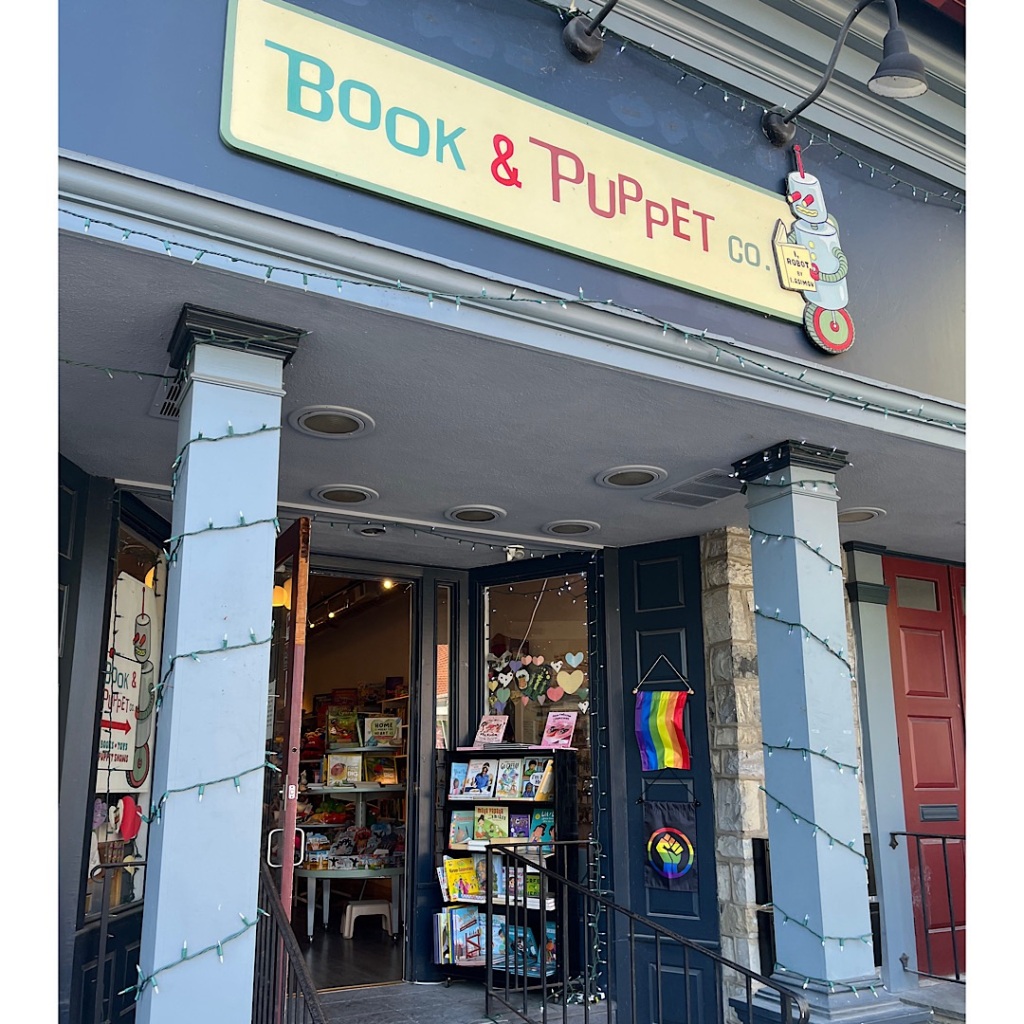

After my adventure at the museum, I meandered to “the circle” to visit Andy at Book & Puppet Company, our local independent bookstore. We had a fantastic conversation and I found the most unusual purchase– a graphic novel rendition of Albert Camus’ autobiographical novel, The First Man. I learned that Andy had produced not only a new CD but also an audio book memoir by Melba Tolliver. Melba had a very interesting career as a television journalist.

And then there was only one acceptable way to end my morning out, with pie from Pie + Tart. I brought the pie home and shared it with the Teenager. I spent the afternoon working on a ghostwriting project and took a break to drive The Teenager to renew her drivers license. In the evening, I returned downtown to have a belated birthday celebration with a friend, poet and former work colleague. We had drinks, guac and other goodies at Mesa Modern Mexican.